Until last fall, the fifth-graders at the John M. Moriarty School in Norwich, Conn., held a monthly cake raffle and bake sale. The PTO-sponsored fundraisers paid for a year-end trip for that grade’s 75-plus students.

But in August, parent group leaders at Moriarty found out about a new state law restricting food-based events at school. Besides the cake raffles, it affected activities from classroom pizza parties and birthday celebrations all the way down to parent group meetings—which had been held during the school day but were rescheduled for 6:30 p.m. to avoid the restrictions.

The most serious effect was on the group’s fundraising. PTO Copresident Colleen Casady explains that leaders spent more on party favors, prizes, and items to sell but raised less money overall because some of the new items were less popular. “Our fundraising went down by $5,000 this year,” she says. For example, at an after-school bake sale with healthy snacks, Casady continues, “we sold a lot less—about a quarter of what we would have if it were brownies.”

Other states have passed similar laws. In spring 2006, the Maryvale Union Free School District in Cheektowaga, N.Y., modeled its own policy on a state law and limited the amount of snacks and sweets available at its four schools. “At the elementary school, they were doing a lot of ice cream parties for rewards, or pizza parties,” says Cindy Strong, who’s president of both the Maryvale Primary PTO and the districtwide PTO Coordinating Council. “Now, we haven’t eliminated the rewards, but instead we’re giving them vouchers for Scholastic books.”

What makes Maryvale different from Moriarty, however, is that PTO participation in the district’s policy is voluntary. “There aren’t any restrictions on us at all,” Strong says. “We still do an ice cream social. We’ve had movie nights where we served pizza.” And for its holiday fundraiser this past December, the group sold cookie dough.

Old Law, New Rules

The same piece of federal legislation, known as the Child Nutrition Act, is behind both Norwich’s and Cheektowaga’s policies. First passed by Congress and signed into law by President Lyndon B. Johnson in 1966, the Child Nutrition Act established the breakfast program in schools and also gave money to states for students who otherwise couldn’t afford to buy lunch (what’s known today as the free and reduced-price lunch program).

Since then it’s been “reauthorized,” or updated and passed again, several times. The most recent reauthorization was in 2004 and added a new piece: Any school using federal money to provide food on campus (such as lunch) was required to create and implement a “wellness policy” no later than fall 2006. It’s been driven at least in part by concerns about childhood obesity; the National Center for Health Statistics reports that in 2003-04, 19 percent of children ages 6-11 and 17 percent of adolescents ages 12-19 were considered overweight or obese.

The law itself is pretty simple. Primarily, each wellness policy needs to include two things: goals for activities, such as nutrition education and exercise, that promote student health; and nutritional guidelines for all foods available on campus during the school day, with an eye toward general student health and reducing obesity.

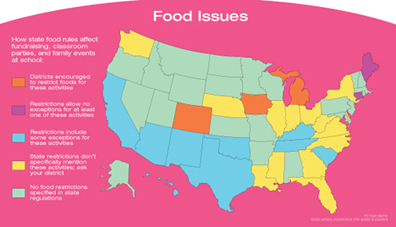

Here’s where it starts to get complicated. Even though the law requiring wellness policies is federal, the policies are actually implemented at the local level. States like Connecticut and New York that have passed their own laws essentially set minimum standards for any local policies. Mostly, though, it comes down to how strictly school districts and boards interpret the legislation.

School boards or other administrators decide what their student-health goals are and how to meet them, and they define minimum nutritional standards for food sold or served on campus. This often includes vending machines, class parties, and the cafeteria. But sometimes it extends to parent group activities, from meetings to family events to fundraisers, even if they take place after school hours or don’t directly involve students.

At Casady’s school in Connecticut, for instance, the PTO reinstated an auction event where parents create themed baskets of items. The auction was in the evening, and only adults were present. Yet the group could no longer include any food, healthy or otherwise, in the baskets because of the wellness policy.

It’s also worth remembering that eating habits are only half the story when it comes to obesity; exercise is just as important, according to health and nutrition experts. Despite that, many wellness policies pay less attention to PE or recess guidelines than to food restrictions. Only seven states have explicit requirements for the physical activity students need to get, and only 12 total do more than “encourage” local policies to include physical activity or recess guidelines.

Parents Should Have a Say

There’s at least one other part of the Child Nutrition Act reauthorization that parent groups should know about. According to the law, parents, students, and other members of the public are supposed to help develop the local policies. Considering the many ways food is involved in PTO activities—most notably product fundraisers that include chocolate, candy, or gourmet edibles, but also carnivals and family nights with popcorn or pizza, holiday celebrations, or even something as simple as brownies at the spaghetti dinner—it makes sense for parent group leaders to be in on writing up the rules that will affect how they go about doing their work.

In fact, the reason the Moriarty PTO in Connecticut and New York’s Maryvale PTO have had such different experiences with their districts’ wellness policies comes down to parent group participation. In Maryvale, a school board member who is also involved in the PTO went to bat for the group, recounting all the ways it helps students and suggesting that it be exempt from the restrictions.

The Moriarty PTO, which didn’t get to contribute to the wellness policy adopted by Norwich Public Schools, now has to find ways to limit or even eliminate the food it offers at activities and through fundraisers. That task has Casady and the rest of the PTO’s executive board worried.

“Kathryn Beich, Sally Foster—they all include chocolate, they all include food. If the catalog includes any of that stuff, the children can’t bring the money [for order payments] to school,” Casady says. “We really do need to get these kids healthy....The reasoning behind [the legislation] is good, but it’s being taken a little bit too far.”

Making the Case

If your group’s activities have been limited by a wellness policy with food restrictions you think are too strict, set up a meeting with the appropriate administrator to talk about the situation. Emphasize the educational activities, tools, and programs made possible by parent group fundraising. Point out the community goodwill and parent involvement resulting from family events, many of which include popular refreshments like doughnuts or brownies. Explain that your group understands how important it is to reduce childhood obesity and teach students about health and nutrition; perhaps even agree to work toward those goals by planning events around those themes (for example, ask a nutritionist to speak during a meeting, or restrict pizza parties to only a few times a year).

Finally, make clear that your group would like an exemption or some flexibility so that it can make the best choices to meet its goals and serve the needs of the school and students. To help show why there should be an exception to the wellness policy’s food restrictions for your group, keep the following points in mind:

- Product fundraisers brought in $1.7 billion in 2005 (according to the Association of Fund-Raising Distributors and Suppliers); the average product fundraiser raised more than $2,500. Food products, including candy, are a popular option driving these results.

- The vast majority of candy sales happen off school grounds, and most candy and other foods sold through product fundraisers aren’t bought by students.

- The 2004 reauthorization of the Child Nutrition Act only requires local wellness policies to cover what students eat during school hours; foods sold or served at any other time don’t need to be restricted.

- Selling or serving “foods of minimal nutritional value” as defined by the U.S. Department of Agriculture—mostly candy and soda—at schools isn’t prohibited by any federal law. The Child Nutrition Act and other regulations only restrict the times and places these foods can be sold. Plus, districts can petition for exceptions in certain circumstances. (See the list of foods at www.fns.usda.gov/cnd/menu/fmnv.htm.)

As any expert will tell you, maintaining healthy habits is about moderation. Offering nutritious foods for school lunches and in vending machines, and limiting serving sizes and the number of times students get candy bars or pizza parties are goals PTOs can stand behind—along with encouraging kids to get enough physical activity, of course. If you can make a case for balancing the wellness policy requirements and the role your group plays, you can help move kids in a healthy direction while also being able to continue the community-building and school-strengthening work parent groups are known for.