Keep Up Your PTO Project Momentum

Tips for organizing long-term PTO projects and keeping volunteers enthused along the way.

We all know how important a PTO is for raising money for events, items, or experiences such as field trips, assemblies, supplemental classroom supplies, and enrichment opportunities.

But sometimes something bigger comes along. Sometimes you’re at the playground and notice that a structure is broken or rusted, or you’re in the library and realize how outdated it is, or you’re volunteering in the classroom and notice that the students have to wait to use a computer.

Join the PTO Today community (it's free) for access to resources, giveaways and more

Can a PTO fund something as large as a playground or a library or computers? The answer is a resounding yes. Such projects might take more than a single school year; they might be a long-term, multi-year investment. But many PTOs have undertaken large projects with great success. It just takes a little extra planning, patience, and enthusiasm.

Get Organized First

Just as students break down large projects into smaller steps, your group needs to do the same. Before you announce to everyone the scope of what you want to do (“We’re going to build a giant new playground that will draw people from the three-county area!”), look at what you realistically can do. Start with researching vendors and estimating the cost. Get parents and students on board early.

Then break down the project into smaller goals and milestones. The schedule may take more or less time than planned, but it helps to have something that keeps people focused and on track.

Slow and Steady

When a couple of moms at Whittier Elementary in Downers Grove, Ill., learned that students were playing on the stumps of old teeter-totters in a playground with some components up to 40 years old, they wanted to install a new one. After learning that the school district was not responsible for updating school playgrounds, the PTA got involved.

“It’s been a long road of research, planning, and fundraising,” playground committee member Carrie Grebel says of the five-year project. They kept plans on track by breaking the project into manageable sections and regularly updating parents and students about the progress.

The first year was spent gathering information. Committee members researched options, cost, and time frames. They presented this information to parents, who were surveyed to determine interest and opinions. The positive feedback the PTA leaders received from the survey (80 percent approved) gave them the validation and confidence to move forward. In addition, parents felt like they had had a say, which was important in maintaining support as time went on.

The playground committee then asked students to draw their ideal playground. While some kids incorporated impractical ideas like a petting zoo and a fountain, overwhelmingly they depicted creative ideas for slides, swings, and monkey bars. Seven popu-lar kid picks were incorporated into the plan. “We tried to meet parents’ needs as much as the kids’,” says playground committee chairwoman Pamela McGinn. “But the design was driven by the children’s voices.”

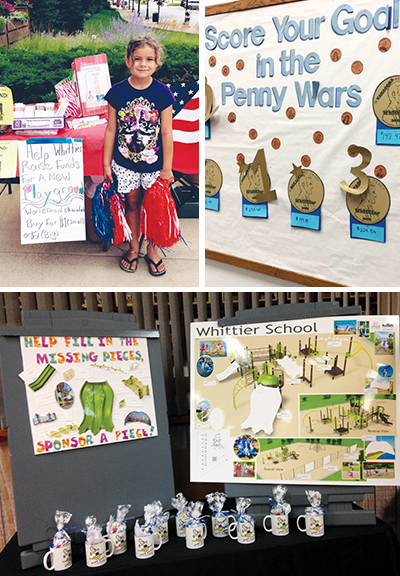

Fundraising kicked into gear the following year. The PTA playground committee aimed to raise $30,000 a year with an overall goal of $100,000. Each year, PTA members voted to allot proceeds from the spring fundraiser to the playground project. They also added a series of smaller fundraisers, such as candy sales, penny wars, and shopper days at local stores. “You don’t want to inundate people, so we kept [each of the minor fundraisers] to a small time period and did some over the summer,” Grebel says.

The PTA website was updated to accept donations, and a flyer went out to all neighboring residents to tell them about the project. Students and parents sold candy at events and festivals in town, raising both support and awareness for the project.

To keep up the momentum, committee members made a large thermometer for the school entryway so students and visitors could see the progress being made. The PTA regularly updated its Facebook page and website. The playground designer made a large drawing of what the playground would look like, and that poster went to all the fundraising events, PTA meetings, school board meetings, and other events in the community.

The vast majority of parents were happy to support the project even if their kids wouldn’t be around to benefit. In fact, the project ended up taking on a life of its own. “It jump-started a larger districtwide discussion with other PTAs,” McGinn says. “We’re currently considering a larger district playground fundraiser to be split among all the participating schools. It’s pretty exciting!”

People Power

Sometimes great projects can be accomplished with very little money; you just have to roll up your sleeves. When Katie Griffin learned that the school library at North Brookfield (Mass.) Elementary had been closed for more than three years, she decided to do something about it. Griffin, now the PTO president, gathered other members and began by simply cleaning the area—wiping down shelves, vacuuming, organizing books, and reclaiming the space, which was being used for storage.

Knowing that fundraisers in the small community were typically not big moneymakers, planners got students involved. They kicked off the project by collecting coins in a Change for Change challenge. Classrooms competed against each other to raise the most money in spare change over a three-week period. While they hoped for a couple hundred dollars, organizers ended up raising $2,000.

When the local lumber store learned what the group was doing, it donated the paint and painting supplies. Parent volunteers spent a summer weekend painting, then decorated the bookshelf ends to look like the bindings of popular books. A cabinetmaker designed a new circulation desk and only charged the group for the countertop.

These efforts and donations, made over the summer, were enough to enable the library to reopen the following fall. The PTO continues to staff the library with volunteers. New books are supplied through proceeds from the school book fair and by donations of new and gently used books from the community.

“We’re in a great town with average to low income,” Griffin says. “The smartest thing we did was ask for help. We try not to do too many fundraisers; we’d rather do events with the kids or send them on field trips.”

Look for Grants

A long-term project doesn’t always take a long time to complete. When leaders of the Fort Blackmore (Va.) Primary PTO decided to replace the school’s old playground, they planned to do it over the course of a few years by buying one piece at a time. They were pleasantly shocked when, despite being one of the lowest-income schools in the county and having only 84 students, they managed to raise money for an entire playground in less than a year.

They started by taking their fall and spring fundraisers and cranking them up a notch with a silent auction and raffle. Then they hit the pavement. “We just got in the car and went to local businesses,” says PTO president Ashley Culbertson. “We wrote a letter explaining the project and then we’d go talk to business owners in person and tell them what we wanted to do and why.”

Culbertson also educated herself on grant-writing. She applied for local and national grants; to her surprise, the PTO ended up with more than $10,000. In addition, some businesses donated $1,000 or more.

In talking to community members and business leaders, Culbertson played up the fact that there was no other playground in the community; families who wanted to go to one had to drive 20 minutes. She was heartened by the support she found along the way. “I found that people in the community really do want to be involved,” she said, adding that she went to the local press, as well. “Tell everyone what you’re doing and why.”

Finding grants to apply for wasn’t as daunting as she once thought. “I just did an Internet search for playground grants and community grants,” she says. She learned that many service clubs and local businesses, such as banks, give charitable donations and grants.

They also saved money by having the PTO assemble the playground. A local family in the construction business offered assistance, as did members of the local Rotary Club and some PTO members. They hosted a large “reveal” to the students when the playground was finally completed.

Fundraising started in fall 2015 and the ribbon was cut just over a year later, in January 2017. “Our community and our PTO really worked together,” Culbertson says. “We did this with only five or six active members. You don’t have to have a huge group. You just have to come together and get out there.”

Eyes on the Prize

When a project requires long-term investments, either financially or through volunteer power, it’s important to keep everyone focused and motivated. Communication is key, both between incoming and outgoing board members and with parents. Celebrate milestones: “We’re halfway to a new playground!” or “The deposit is down for our new electronic sign!”

Finally, don’t rule out broader community support. Grandparents may bring their grandchildren to the playground or may want to shelve books. Parents of older students may want to give back. Ask and explain—and then get to work.

8 Tips for Keeping Support Strong

Do your research—and plan accordingly. Big projects involve lots of details, and how you approach those details can have a significant effect on cost and timeline. Make sure you know what’s ahead before you jump in.

Get broad support from parents early. Giving everybody a say early on builds momentum and is invaluable for maintaining support over the long term.

Get students excited. When students are excited about a project, they can have a big influence on adults. And in the right situation, they can be great at promoting your project.

Seek out grants. Especially in lower-income communities, grants can be a major source of funds for your project.

Let the community know what you’re doing. It’s likely that people beyond your school will be interested in helping on a major project that will have lasting impact. And your broader community has resources and expertise that you can’t access if you just share your message within the school.

Approach local businesses. Larger businesses may be willing to donate money for the right project, while smaller businesses will often make in-kind donations like paint, equipment, or labor—free or at cost.

Use elbow grease when possible. Sometimes attacking a project with hard work can cut a significant amount off the price tag.

Trumpet your progress, good or bad. Let the community know how you’re doing. You want them to have a vested interest in the success of your project, too.